Universal Life Insurance

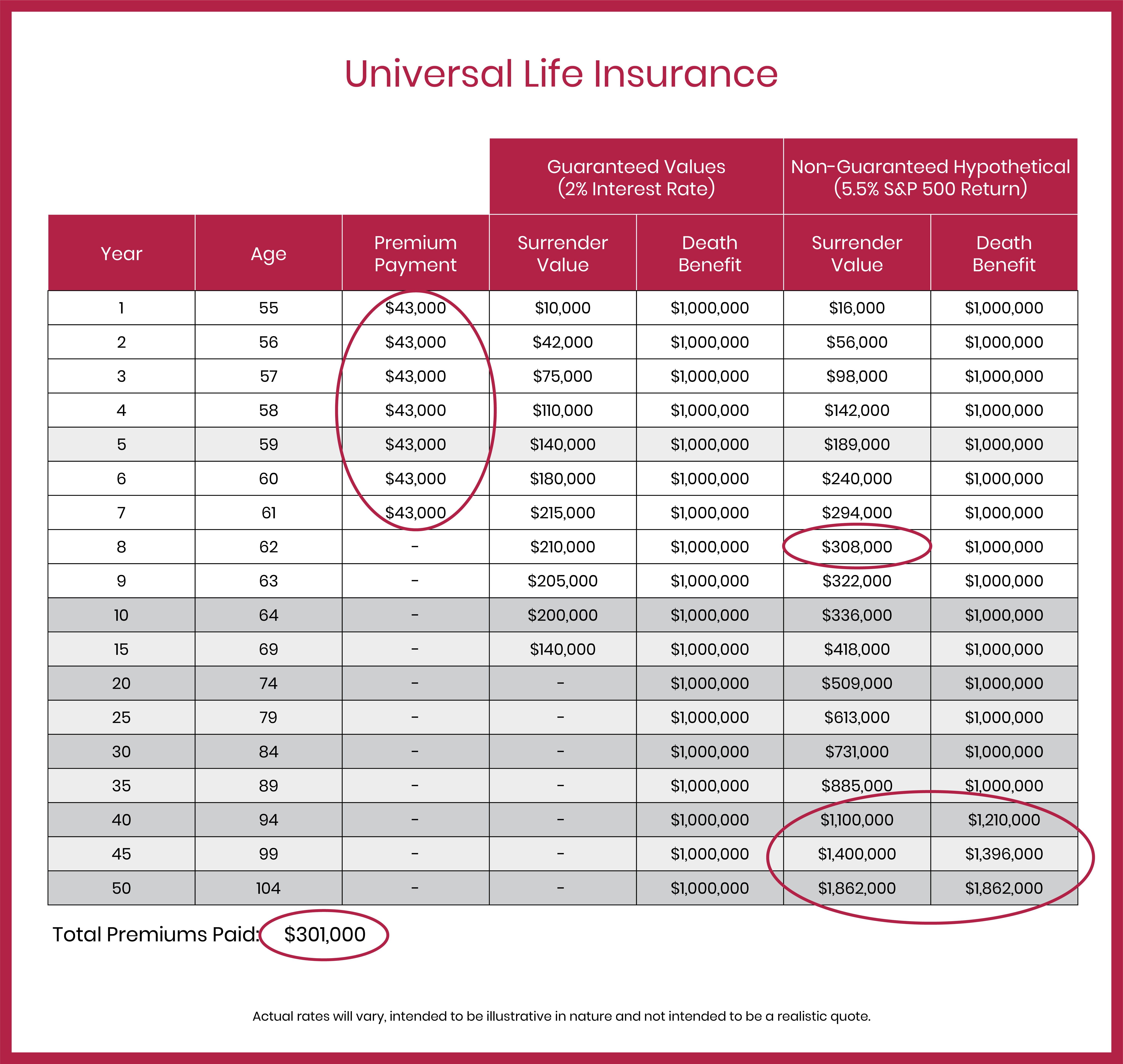

Universal Life (UL) is a type of permanent life insurance with both a death benefit and a cash value (i.e. investment feature) that can grow tax-deferred. The annual payments can vary, with a portion going to the premium and a portion going to the cash value. Once the cash value is large enough, it can self-fund the premiums through the annual returns on the cash balance. A policy designed for 5 years of payments is called a “5-Pay” policy, a policy designed for 7 years of payments is called a “7-Pay” policy, and so on. The following illustration shows a 7-Pay policy. The first 10 rows show the first 10 years and the results in 5-year increments are shown thereafter.

True to its name (“7-Pay”), there are only 7 years of premium payments. These are $43,000 each for a total of $301,000. Note that the table shows two scenarios “Guaranteed Values” and “Non-Guaranteed Hypothetical.”

Guaranteed Values

The values in the “Guaranteed Values” columns represent the worst case scenario. The cash value is designed to follow the S&P 500 (subject to a cap); however, a 2% return is guaranteed in case the stock market does poorly. In this scenario, the surrender value grows during the first 7 years while the premiums are being paid, but once the payments stop the accumulated cash value gradually decreases as it is used to pay the ongoing cost of insurance.

While it seem like the policyholder is “losing” somehow because the cash value is shrinking, it’s really just that the premiums are being paid out of the accumulated cash value. No matter what the return is–whether 2% or 200%–the accumulated cash balance would still be used to make the ongoing insurance payments, but in this worst case scenario the guaranteed minimum interest rate of 2% does not provide enough gain in each period to fully cover the cost of insurance.

For a typical UL policy, once the cash balance is drawn down to zero, there’s nothing left to draw on for the premium and the policy lapses, but in this case, the policy has a “Death Benefit Guarantee” rider that’s included in the cost of the initial premiums. As a result, the death benefit stays in effect until the policyholder turns 105 years old!

Non-Guaranteed Hypothetical

The values in the “Non-Guaranteed Hypothetical” columns show just one of the many scenarios that have the potential to unfold. This example assumes an annual return of 5.5% for the S&P 500 and historical cost of insurance figures. With the higher 5.5% return, the growth in the cash value is more than enough to cover the cost of insurance. Consequently, the cash value keeps growing even after the out-of-pocket premiums stop. Once the cash value surpasses the death benefit, the death benefit itself begins to rise. As a result, when the policyholder passes on, the larger accumulated cash value ($1.8 million at age 104) is what the beneficiaries receive tax-free.

The other thing to notice is that, between years 7 and 8, the cash value in the second scenario has accumulated enough to cover the total amount of premiums that have been paid. This creates what we call a “free look-back,” where the policyholder can reassess at that time and decide whether or not it makes sense to keep the policy in effect at that time. If the decision is to cancel the policy, the policyholder can walk away with his or her money back. All the while, though, he or she would have benefited from “free” coverage with a $1,000,000 death benefit. In our view, that’s a pretty good deal.

Related to the “free look-back” is the uncertainty surrounding what will happen to the currently high estate tax exemption when it is set to expire on Dec. 31, 2025. Will it be allowed to expire? Will it be extended? Will it be modified in some unforeseen way? Establishing a “7-pay” or similar policy now will allow a policyholder to setup the policy essentially for free (assuming the 5.5% S&P 500 return scenario) and decide whether or not to keep the policy in place once the uncertainty around the estate tax exemption has been resolved.